How did history forget Howson — a basketball trailblazer?

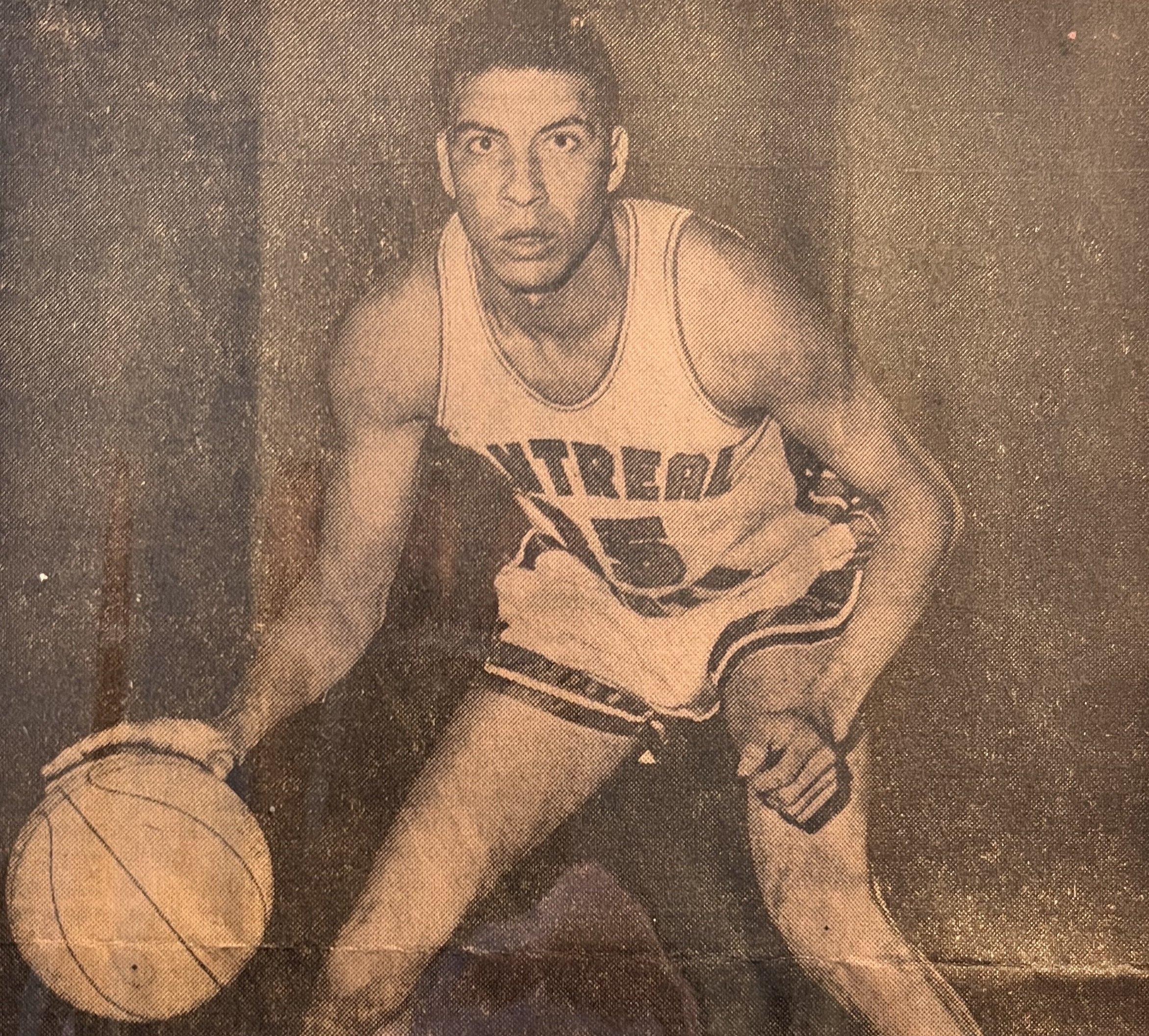

Olympian Barry Howson, who grew up in London, was a Canadian hoops pioneer. The first Black player on the country’s national team, it’s past time he got his due.

* * *

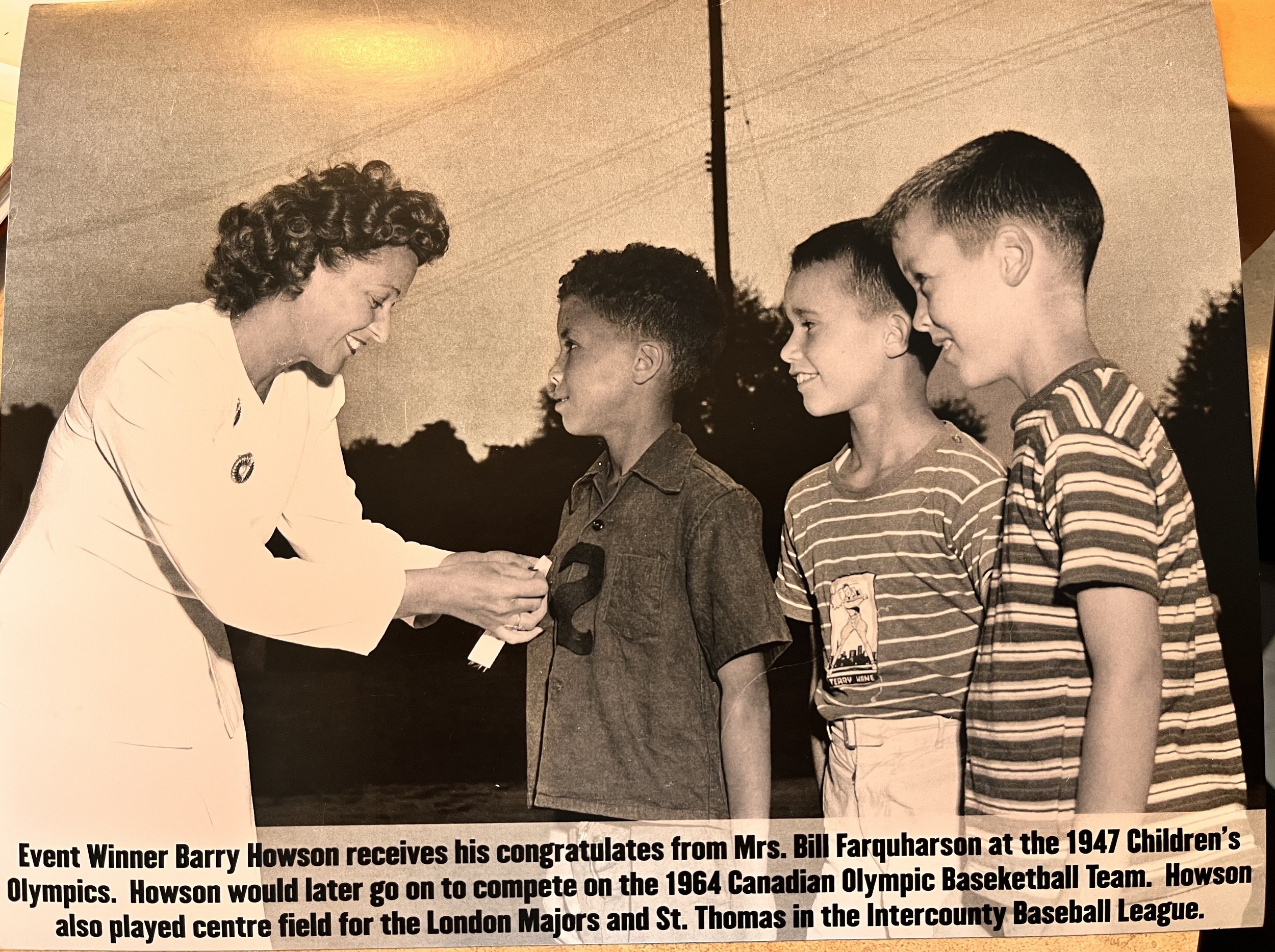

He was the fastest kid on Glenwood Avenue.

A gangly lad living and playing in a Black corner of the city where the streets were constantly filled with kids – connected less by the colour of their skin, and more by the poverty hanging over their homes. He was one of the lucky ones – running water and an indoor bathroom, a rarity in a neighbourhood dominated by water pumps and outhouses.

Barry Howson’s East End was the rough end, the tough end, of London, even in the 1940s. But that’s where the kid came of age leading the pack racing down Glenwood every Sunday afternoon after church, looking to claim his nickel prize money for finishing first.

Little did the friends and family watching along the dusty roadside know, that kid would grow into one of the city’s most talented and significant athletes.

Howson lived up to his family name, near royalty when it comes to Black Canadian trailblazers. His path took the Forest City native to courts both across Canada and halfway around the world to carve his name into basketball history – a history largely ignored and overlooked by the sporting establishment.

* * *

LONDON, ONTARIO, 1931

This could easily be a story about his momma.

Christine Jenkins Howson’s family came to Chatham from Priceville, Ont., a village in Grey County about 160 km northwest of Toronto.

Let’s talk about the significance of this region for a moment. Collingwood, like the town of Owen Sound situated about 65 km to the west, served as a crucial point along the Underground Railroad during the 19th Century. This clandestine network, comprising Black, white, and Indigenous volunteers, aided in the escape of approximately 30,000 to 40,000 formerly enslaved African Americans from the United States to Canada where slavery had been abolished on Aug. 1, 1834.

Between 1820-50, approximately 1,500 Black people who were either free or formerly enslaved settled in the expansive region known as the Queen’s Bush, which extended from Waterloo County to Lake Huron. Among the various settlements within the Queen’s Bush was Priceville, where freedom seekers like Howson’s mother’s family made their home.

According to the 1851 census, every 50-acre plot along Durham Road in Priceville was occupied by a Black family, with parents born in the United States and most of their children born in Upper Canada. The village was small – a schoolhouse, a church, a cemetery.

However, the once-thriving community of the 1850s, brimming with hope and potential, had essentially vanished by the 1880s. By the 1930s, any visible remnants of a Black presence in Priceville had been plowed under and turned into fields.

Families scattered across Ontario, with many, like Christine’s family, ending up in Chatham.

Christine DeGroat was born on March 8, 1898. Her parents, Michael and Elizabeth Harris DeGroat, initially raised their children in Kent County community, before moving to London.

In the Forest City, Christine grew up and married James Jenkins on April 30, 1913. They had eight kids. Together, the couple ran The Dawn of Tomorrow newspaper, a Black Canadian newspaper founded in 1923 in London. Its cross-country circulation reached 5,000 readers at one point during its run until 1971.

The Dawn did not shy away from a fight, be it calling out London restaurants for refusing to serve Black customers, to challenging the Black church to do more for its people. Overall, the publication dedicated itself to documenting local news related to Black Canadians, including significant events such as the establishment of Canada’s first Black Boy Scout troop. Moreover, it placed notable emphasis on showcasing achievements by Black individuals in music, theatre, education, and, yes, sports.

Its motto: “Devoted to the interests of the darker race.”

The Jenkins were an activist family before we even knew what that was. In 1924, James Jenkins established the Canadian League for the Advancement of Colored People (CLACP), a Canadian equivalent to the NAACP, with branches in London, Windsor, Dresden, and Toronto. Although the CLACP did not achieve nationwide recognition, it played a crucial role in supporting local Black Canadians by facilitating job placements, professional opportunities and youth education, and providing assistance and resources to those in need.

James Jenkins died of appendicitis in 1931 – it devastated his wife, who laid on her bed for three weeks, despondent, lost, and unable to work as a Depression raged outside the home. Finally, she heard a voice that called to her: ‘Come on, Christine, you gotta get up and look after these kids.’

“That’s when she realized she had this treasure with her – and restarted the paper,” Barry Howson explained.

For the next 40 years, Christine Jenkins Howson’s exact influence is difficult to measure, as most of the newspaper’s stories are unbylined. But it is not an exaggeration to say she’s among the most important Black women in 20th century Canada, and one of the most pioneering journalists in the nation’s history.

* * *

TOKYO, JAPAN, 1964

Hosting the first Olympic Games in an Asian country, Japan eagerly sought to demonstrate its recovery from the ravages of the Second World War. A clear manifestation of their successful reconstruction was evident in the choice of Yoshinori Sakai as the final torchbearer. Born Aug. 6, 1945, in Hiroshima, the day the atomic bomb devastated the city, Sakai symbolized both a tribute to the victims of that fateful day and a fervent plea for global peace.

The Tokyo Games marked the end of an era for the Olympics in many ways, with the retirement of the use of a cinder running track for athletics and hand timing by stopwatch. Among the notable sport debuts were judo and volleyball, with the latter representing the first-ever appearance of a women’s team sport. Canada took full advantage of judo’s inclusion, as Doug Rogers secured a silver medal.

Rowers George Hungerford and Roger Jackson earned Canada’s solitary gold medal. A tandem affectionately known as the ‘Golden Rejects,’ the pair were originally considered alternates, only beginning training as a pair just weeks before the Games. Given little chance of winning, most Canadian officials and journalists skipped the event, only to later discover that Hungerford and Jackson had clinched gold by an impressive three-quarters of a boat length. Additionally, Canada secured two more medals on the track, with Bill Crothers earning a silver in the 800m and Harry Jerome capturing a bronze in the 100m.

When it came to basketball, however, Canada should never have been there in the first place.

* * *

LONDON, ONTARIO, 1939

When she became pregnant by a white plantation owner in North Carolina, a young woman fled The South and traveled to Canada where she abandoned her newborn at an orphanage in Toronto – not an unheard-of practice at the time, and certainly not for a mixed-race child.

The unknown infant was given the name ‘Franklin Smith.’

Only weeks later, Franklin was adopted by Askin Street Methodist minister W.G. Howson, a father to four daughters and a man who desired a son so badly that he traveled from London to Toronto and adopted the infant.

Raised in the Forest City, the now-named Franklin Howson eventually met and married Christine Jenkins and had Barry, their only child together, in 1939, raising him along with Christine’s previous children in the family home.

Franklin Howson was injured during military service. A double-hernia loading artillery shells brought him home where he went to work for the L&PS railway, cleaning the passenger cars making the electrified London-to-Port Stanley run. He was a popular man in the neighbourhood. Although not big in stature – only standing 5-foot-4 (Barry credits his mom for his height, as she was 5-foot-7) – he was full of life and energy, known for his massive birthday parties on July 17 each year.

Barry Howson’s childhood is not only tucked neatly into scrapbooks, but also easily accessible in his mind – from yellowed newspaper clippings, to dozens of sepia-toned photographs, to an endless stream of keepsakes and ribbons, to volumes of memorized stories.

Drawing back seven decades or more, Howson can recount playground challenges, school competitions, and track meets at Labatt Park where city championships were held every year. He remembers his teacher providing a bolt of cloth to take home, where his mother made him a pair of shorts and a sash to compete in.

“Track made me the athlete I was. What sports don’t you run in? What sports don’t you jump in? When you’re in the neighbourhood, you play, you run, you jump. We were conditioning since an early age – we didn’t know that, of course. We were just having fun.”

The Howson family lived at 95 Glenwood Ave., in the heart of Black London, a vibrant area of hard-working families. There was one white family on the block, the Aarons, and they had a pony. The neighbourhood was full of kids who, each morning, would walk to school together.

Howson grew up just a few doors down from the Andersons, who had a few kids Londoners came to know well. Stan ‘Gabby’ Anderson became a London Majors star in the 1940s and 1950s, and Frankie Anderson, a boxer and hockey standout, was famously known as owner of London Chicken Coop Boxing Club.

Howson never thought about race growing up. In fact, the only difference he felt from the kids around him was that his family was a bit better off given a two-income home.

In fact, race has always made for odd footnotes in Howson’s life. L&PS railway employees like Franklin Howson were given an alien border crossing ID to make for smoother passing over the border given that their work took them back and forth several times a day.

The cards listed race. Barry’s father was listed as white. His mother listed as Black. The light-skinned young Howson was listed as white. These determinations were based on the colour of the skin, no deep dive into family ancestry, because doing so would reveal the complexities of race at the time. For Howson, it would have revealed a half Black-half white father, and a Black mother with white and Indigenous ancestors.

“I am quite the mix,” Howson said. “The colour of my skin. My high cheekbones. I have Black blood, Irish blood, Indian blood.”

Best just call the kid ‘white’, the railway thought, and move on.

* * *

LONDON, ONTARIO, 1957

Howson first picked up a basketball on the playgrounds of London. Drawn to the game at a young age, he installed a wine barrel hoop and backboard made of planks in his backyard. He played day and night.

His first taste of success came at Ealing Public School, where he won a city championship for basketball in Grade 8.

When it came time to pick a high school, Howson went his separate way from the other neighbourhood kids. At the end of the street, he split from the pack, most of whom turned to go to Beal Tech. Howson walked the other direction to Beck.

Beal was a massive tech school of 1,500 kids. Beck was a more academic institution. Although dramatically smaller, at 500 students, the opportunities for sports were far more plentiful.

In Grade 9, Howson was already the fastest kid in the school. He played football, track, and basketball.

After failing to make his Grade 9 team, Howson spent the year playing hoops and lifting weights at the YMCA. In Grade 10, he was selected as “one of the spares – the 13th guy on a 15-player team that only dressed 12.” But when a teammate got injured, Howson got bumped up a spot to the traveling squad for a tournament in Tillsonburg.

There, Howson logged a lot of pine time, not seeing the floor at all for the first two games. He finally got into the third and final game, taking the floor to start the second half. He proved too much on defense, picking the opposing guard’s pocket, and scoring time after time. That got the coach’s attention. He wrapped the year as the second leading scorer among junior varsity players in the league.

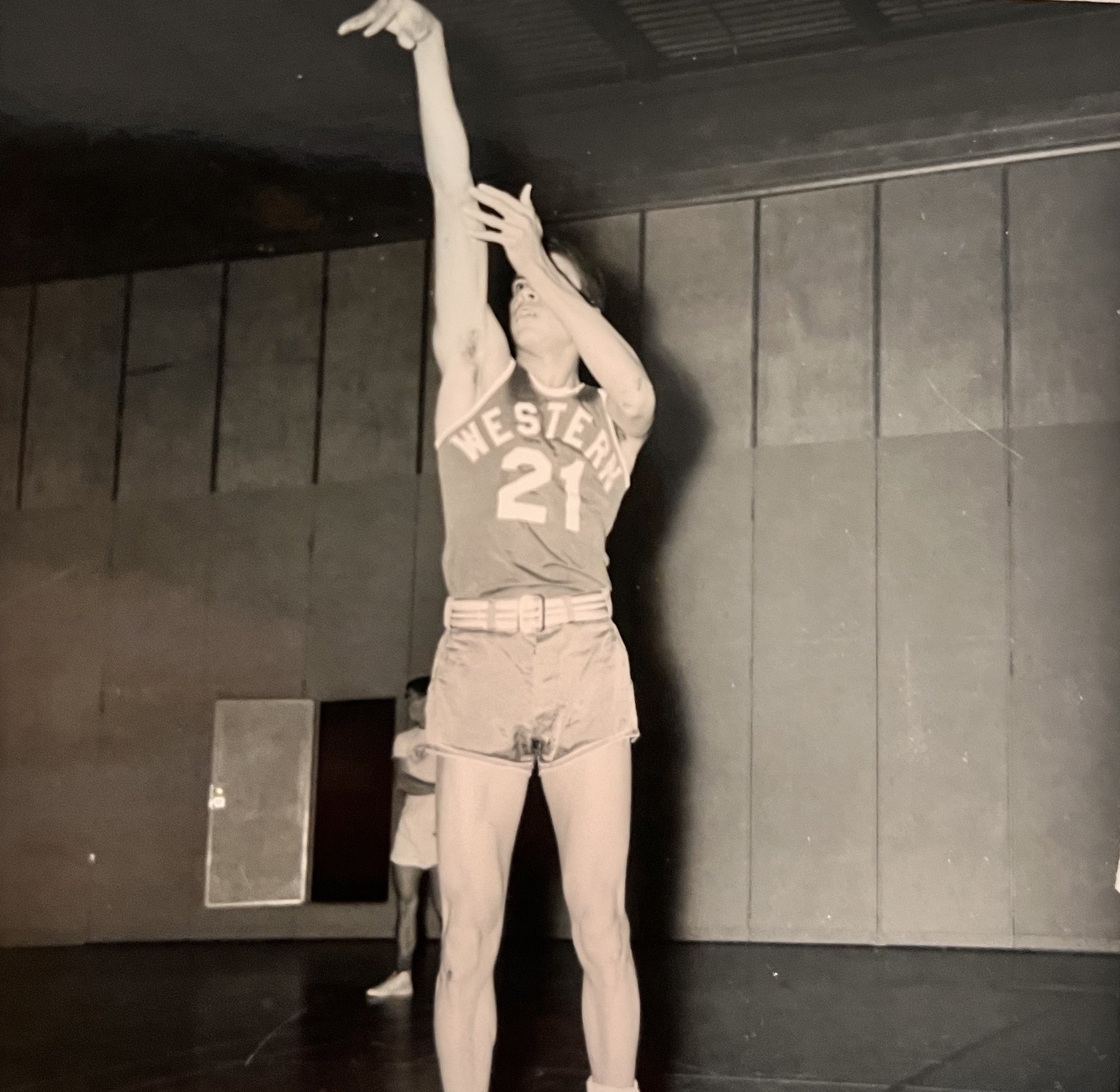

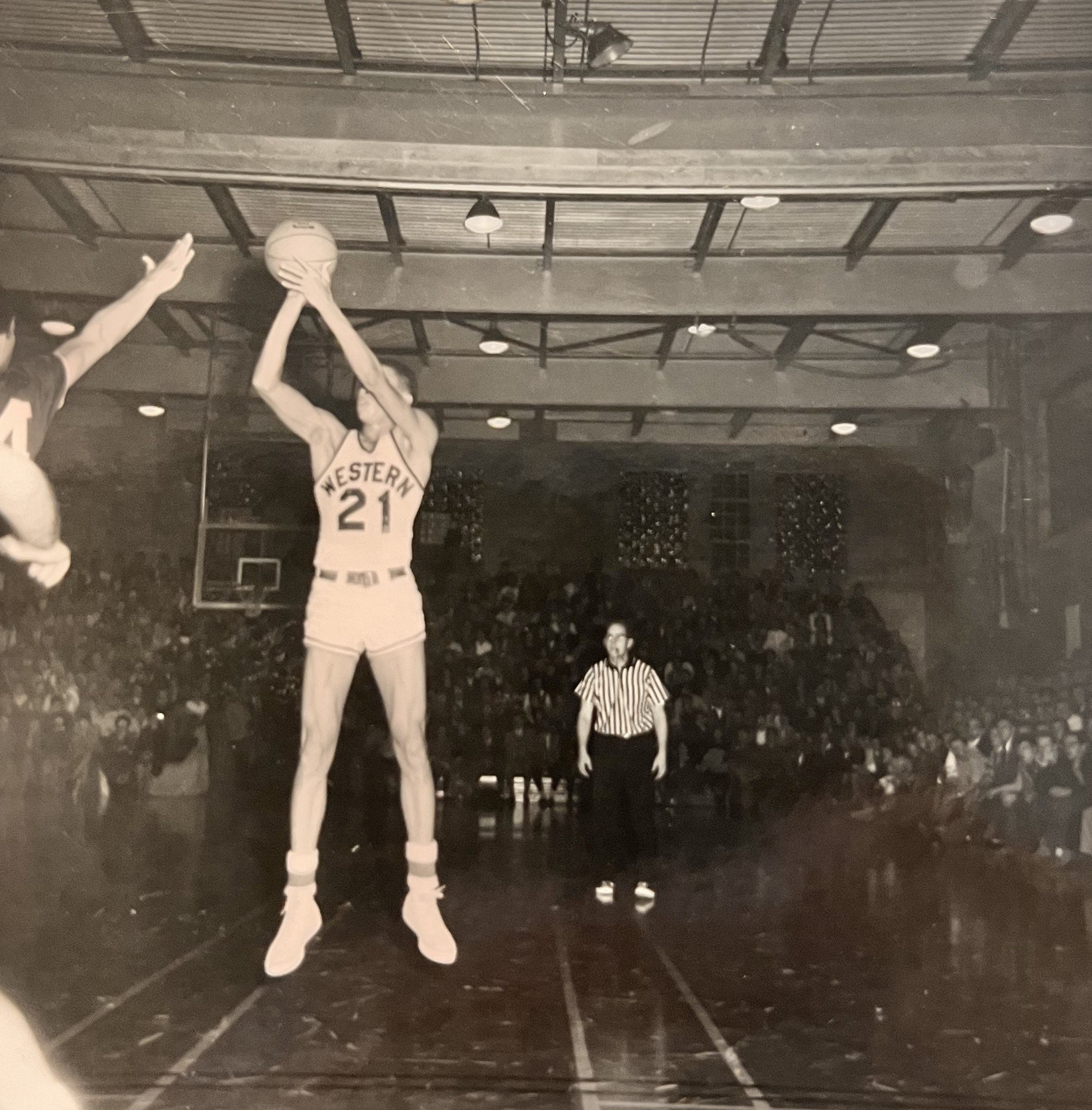

In Grade 11, Howson joined the varsity squad – again relegated deep on the bench. But when he volunteered to play centre on a team that lacked one, Howson was catapulted into the starting five.

In the middle, his athleticism shone through as clearly as the jersey number on his chest.

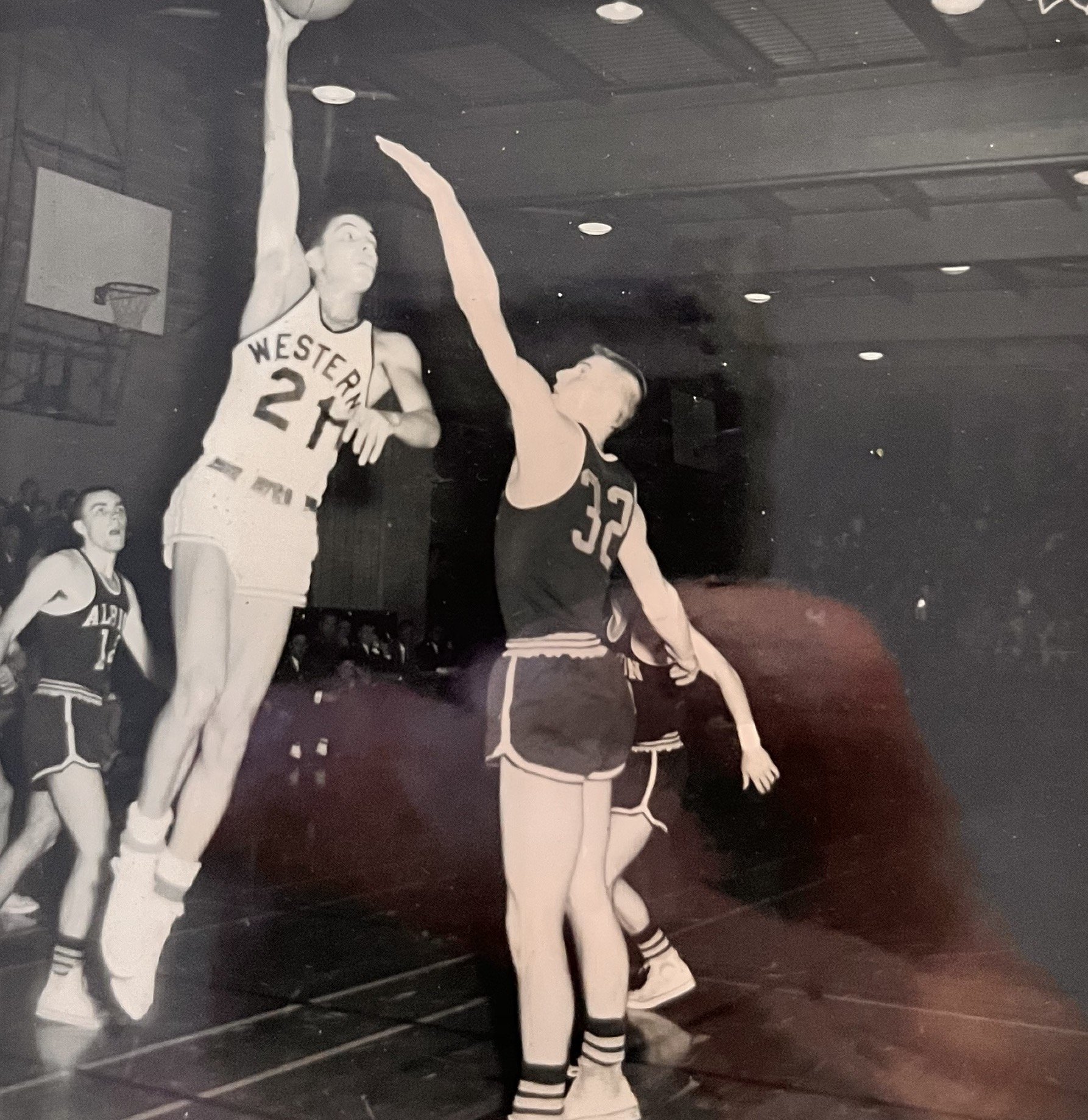

The stringy, 6-foot-2 lad was quicker and more agile than most centres who couldn’t matchup with him outside. Yet, he was big enough to dominate smaller, quicker players on the inside, too, with a delicate hook shot that worked as well from two feet as from 20, with a soft bank of the backboard – a shot that was frequently captured in newspaper photos. Howson could touch the rim with his elbow in the days when dunks were still illegal. But that vertical made him a formidable shot blocker, often snagging shots out of midair.

His kneepads showed the wear of a tenacious defender who loved to dive after balls.

He was also a mentally tough kid. Before every game, Howson stayed behind after the team went out to warm up. He stepped into the bathroom and stood in front of the bathroom mirror. “I would look into my eyes and think and think and think. What do I need to do. It was a self-hypnosis. Then I would come out calm, cool, and collected. That was my focus. The body needs a mental warmup as well as a physical one to be able to focus.”

In 1957, Howson led Beck to an All-Ontario Championship, the only London school ever to accomplish the feat.

Under Head Coach Roger Macaulay, Beck represented the London Conference (a precursor to the Thames Valley District Athletic Association) in the All-Ontario final. Beck was a star-studded team, comprised of an all-star starting five with a deep bench. In addition to Howson, the team included Brian Laird, captain Gerry Witherden, Gary Boug, Tom Timbrell, Bill Woloshyn, Walter Turek, Larry Fazakas, Ken Earthy, Dave McLeod, John McNaughton, and Jack Wistow.

Beck played a different brand of basketball than most high schools of the time. They were fast, they took chances, and while they gave away a few baskets deploying that style, they more than made up for it with the opportunities it created.

Howson was one of two standouts on the team, along with Boug, that drew the eyes of hoops observers during that championship weekend in March 1957.

After three years of competing in the tourney, and finishing as runner-up the previous year, Beck found its way into the Finals after a 51-50 victory of Welland Notre Dame and a 57-45 upset of Sudbury Tech.

Against Sudbury, Howson was limited to only 10 points, but his defensive effort shut down a Bluedevils team that towered over Beck.

Beck topped Toronto East York 67-35 in the final to capture the Golden Ball Trophy. A 29-7 run in the third quarter ended any doubt for the London squad. Howson led all scorers with 26 points.

On Sunday night following the championship, Beck students raced to the CNR station in downtown London and “shattered the still of the Sabbath with school songs,” according to the London Free Press.

The following Monday, the Free Press celebrated the championship with coverage of both the Beck student celebration and a weekend tourney recap with stories written by the legendary sportswriter Bob Gage.

On the walls of the station hung huge green and white banners. Gage reported on a crowd that gathered and grew impatient waiting on their champs. When the players arrived, led by their coach with championship trophy in hand, they were greeted by Will Rice, Beck’s athletics director, school cheerleaders, and hundreds of students who showered the crowd in confetti.

A spontaneous victory parade nearly took off up Richmond Street, but the crowd settled into the parking lot as the local heroes were picked up, one by one, by their families.

In one photograph in the paper, Howson can be seen poking his head from behind the Golden Ball as it was presented by W.K. Bailey, President of the Ontario Federation of Secondary Schools Athletic Association (OFSAA).

Almost seven decades later, it’s still the only prep hoops championship won by a school in the city.

In 2008, that Beck team was inducted into the London Sports Hall of Fame.

* * *

TORONTO, ONTARIO, 1964

Because Team Canada’s men’s basketball team failed to qualify for the 1960 Rome Olympics, the team did not receive any financial support from the Canadian Olympic Association (COA) or the Canadian Amateur Basketball Association for the 1964 Pre-Olympic Basketball Tournament in Yokohama, Japan.

“Not a dime,” Howson said.

Arguably, that decision was understandable. Canadian basketball hadn’t been a great investment in recent decades. Prior to failing to qualify in 1960, Team Canada had finished ninth at its three previous Olympic Games (1948, 1952, and 1956).

That lack of support, however, meant that the team had to raise money on their own for everything – from uniforms and ceremonial blazers, to plane flights and accommodations. Players wrote hundreds of letters and made countless phone calls, but only raised about $6,500. That meant the players – normal guys with jobs like teachers and salesmen, pharmacists and grocery store managers – had to pull hundreds from their own pockets to compete for their country on the world’s biggest stage.

Even up until a month prior to leaving for Japan, the squad was looking for a Canadian flag to carry in the Opening Ceremonies. Manager Doug Heaslip placed a call to a City of Toronto politician who promised $1,000 to buy a flag, pennants, souvenirs, and blazers for the team. That money never showed up.

“We figure we’re going over as goodwill ambassadors for Canada and you’d think that somebody, some government agency, at least, would give us a flag or, at least, the money to buy one,” Heaslip told Jack Sullivan of the Canadian Press. “This whole thing is ridiculous, and the fellows are starting to take the attitude ‘the hell with it.’”

Heaslip continued, “Our guys just wonder about this whole thing. I read where it cost $25,000 to police the Beatles visit to Toronto, and yet they can’t give us a lousy $1,000. People just don’t seem to realize that we are going over there to represent Canada. If we turned up in Japan and played in Bermuda shorts, there’d be one big fuss made in Canada, but we’ve bought uniforms, blazers and so on and nobody will be ashamed of us.

“Even if we don’t win a game, we are still representing our country. And we’ve even got to buy our own flag to hoist up in the pole along with the flags of other competing countries … We took a calculated risk financially and we will pay all our bills. But it gets a little thick when we have to buy our own flag.”

* * *

LONDON, ONTARIO, 1962

Even before the Beck championship, Howson was already attracting attention as one of the top prep athletes of his generation in Ontario. He had already declined offers to try out for the Detroit Tigers when American colleges began recruiting him to play hoops. That’s when John Metras came knocking:

‘Mrs. Howson, I understand Barry is going to The States on scholarship to play basketball.’

‘He is.’

‘Well, he doesn’t need to do that. He can go to Western.’

‘We cannot afford Western.’

‘We can handle that.’

Howson still laughs at the thought of the legendary coach sweet-talking his mother. Thanks to Metras’ strong arm, and the support of a wealthy unnamed alumnus, Howson was able to take his talents across town rather than south of the border.

“I was relieved, if I’m being honest. I got to play basketball, get an education, and stay home with my mother.”

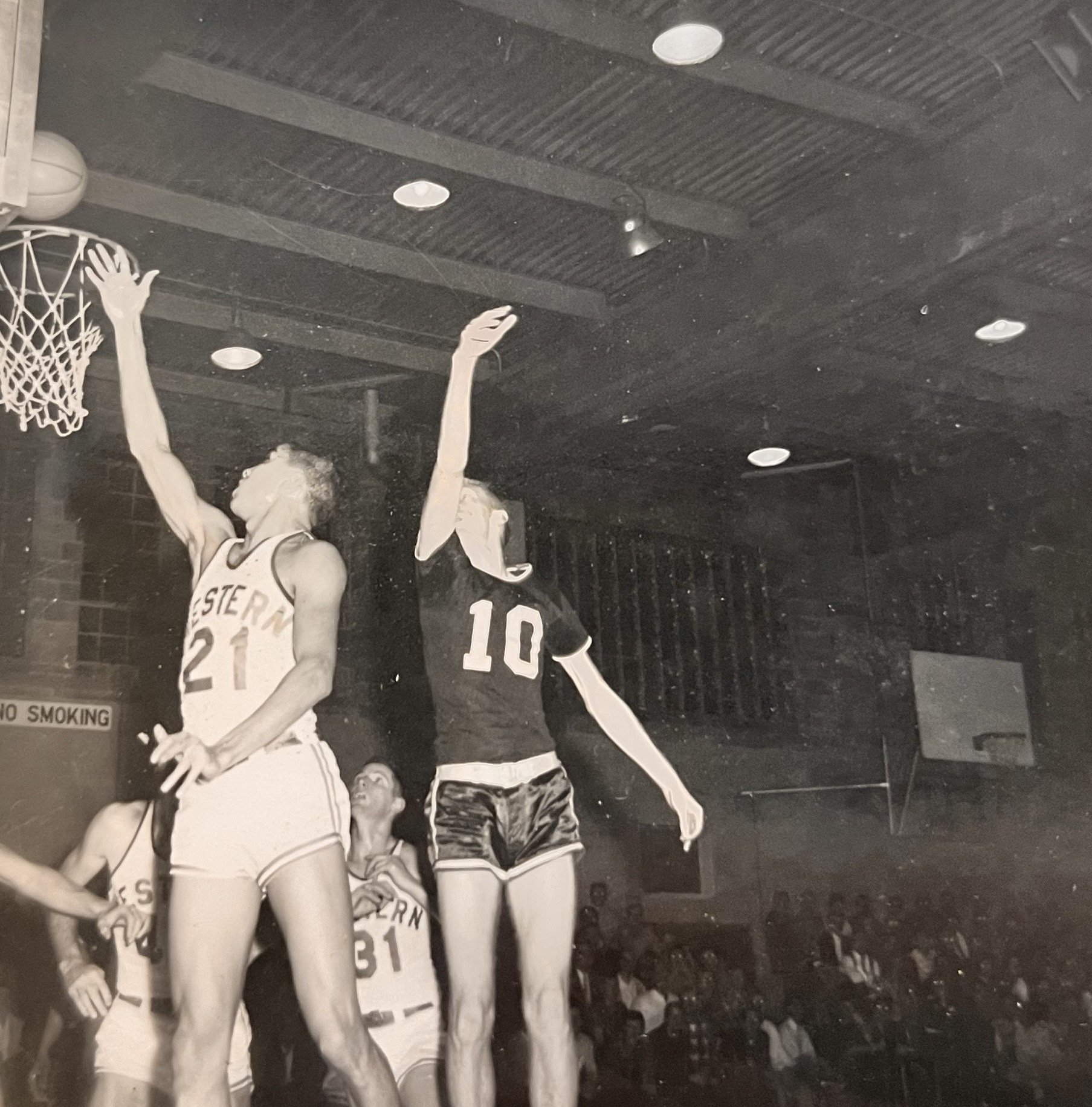

At Western, Howson was coached by the biggest of names in Purple and White history, with Jack Fairs leading his freshman squad, and then Metras awaiting him when he moved up to varsity.

Howson remembers Metras as a coach with a bark worse than his bite, a dogged recruiter who got every athlete he wanted, by whatever means necessary. “He was so good at recruiting, got so many great guys, that he didn’t need to do much coaching,” Howson laughed.

Howson still holds many pleasant memories from his university days. He loved King’s University College, a close-knit community with classrooms dominated by his fellow athletes. Playing in the Forest City also had the off-the-court benefit of his mother getting to see him frequently. He greeted her from the court each time she arrived with a huge ‘Hi, Mom!’ after forgetting to do so on one of her earliest visits to see him play.

From his home, Howson rode the bus from the east end to campus – Hamilton Road, down Richmond Street, through the Western Gates. It was a 40-minute trip in the best of times. Often arriving just in time for games, he pushed his commute a bit close once when a fire at Oxford and Richmond streets delayed the bus. He arrived at Thames Hall gym in front of a packed house after the game had started. “Howson!” he still remembers Metras bellowing to this day. “Three laps around the court.”

The 1960-61 Mustangs won the Ontario-Quebec Athletic Association (OQAA) championship behind high-scoring performances from Howson. They repeated in 1961-62, earning Metras his 14th league championship in 19 seasons on the bench.

Again, despite being the lone Black player on the squad, Howson said he experienced little discrimination. Sure, crowds often targeted Howson – not because he was often the only Black player on the court, he explained, but because he was often the best.

Howson’s Olympic dreams could have started four years earlier, while still at Western, when he competed in the Canadian track and field Olympic trials in Saskatoon in July 1960.

Earlier that summer, he jumped to prominence when he cleared 6-foot-3 in high jump and defeated former Canadian Olympic competitor Ken Money in the Eastern Canadian Championships.

Although invited to the Olympic trials, Howson nearly missed the opportunity – if not for the last-minute support of Labatt’s picking up his plane ticket and the PUC Recreation Department granting him the time off from his summer job. Even still, it took a call to Paul Pose of the Central Ontario AAU selection committee on the day before the event for Howson to be granted a last-minute spot.

He finished third in the high jump trials and failed to qualify for the 1960 Games in Rome.

While playing at Western from 1960-62, Howson also split his time on the amateur hoops circuit, an organized, if not somewhat regional, pursuit with Senior A and Senior B squads scattered across the country. Howson won back-to-back Eastern Canadian Championships in 1961 and 1962 with the Tilsonburg Livingstons-London Fredericks and the Montreal Yvan Coutu Huskies, respectively.

He landed eventually with the Toronto Dow Kings, the team that would lead him to the Olympic Games.

After graduating from Western, Howson also began a lengthy high school teaching career than spanned over four decades.

* * *

TORONTO, ONTARIO, 1964

Despite opting against sending a basketball team to Tokyo in 1964, the COA gave the Dow Kings squad the go ahead to play in qualifying tournaments if it wished – all at its own expense. If they somehow made the Games, the COA would pay for it.

Or so they said.

For Howson, the penny-pinching to travel to the Olympics meant moving to Toronto during the summer leading up to The Games, where he lived with his sister and worked at Dow brewery. Working the bottle line, Howson ran afoul of union bosses who scolded him for working too quickly, and he was soon fired. He finished the summer unloading trucks for a stationery and cards manufacturer. All this just to pay for his own $500 plane ticket and Opening Ceremonies outfit.

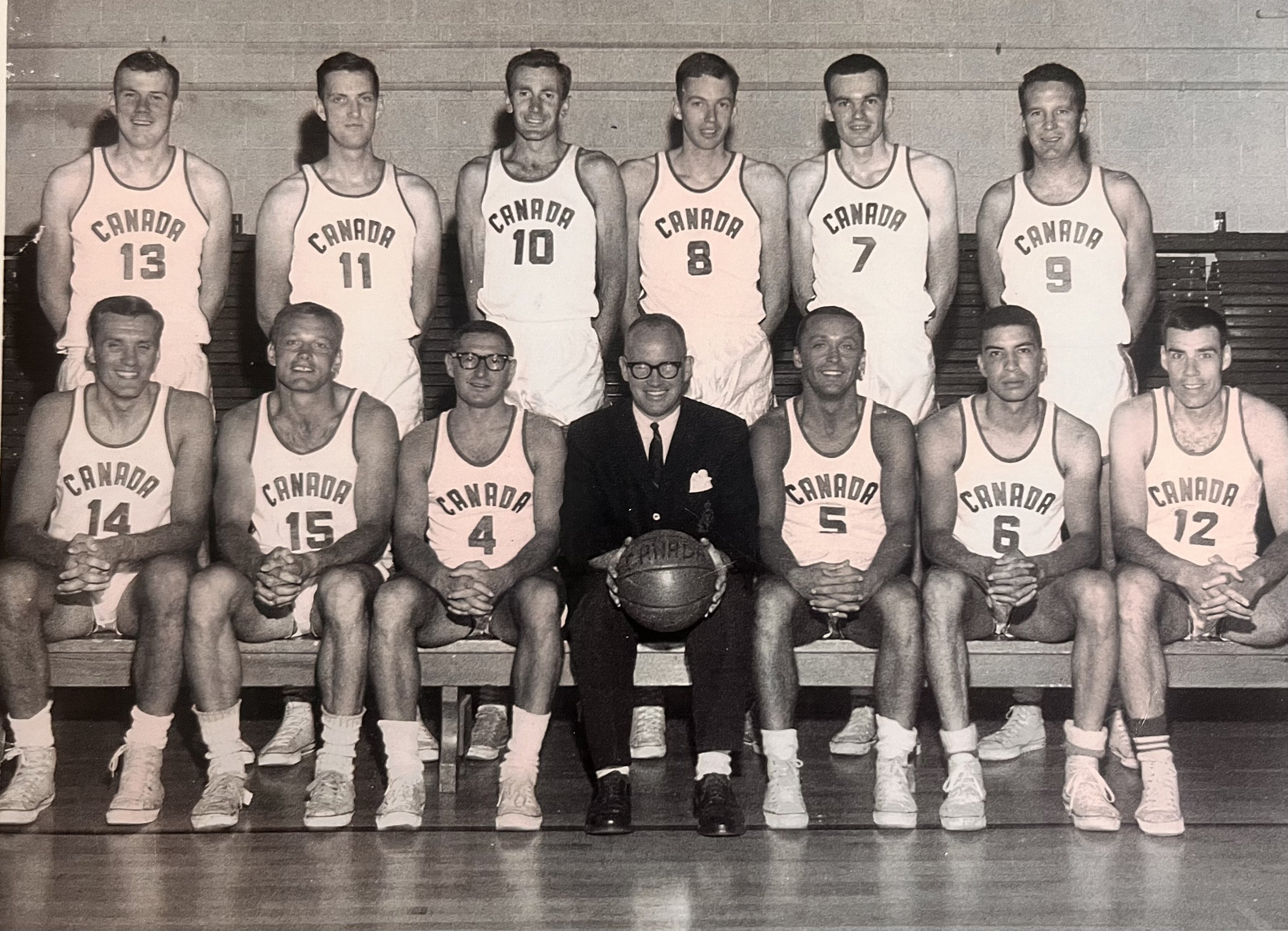

The team was largely composed of players from the Dow Kings, winners of the 1963-64 Canadian Senior Men’s Basketball Championships, including:

Allan Birtles, #10, Carbon, Alta.

John Dacyshyn, #14, Toronto Dow Kings, Etobicoke, Ont.

Rollie Goldring, #11, Toronto Dow Kings, Scarborough, Ont.

Keith Hartley, #8, Toronto Dow Kings, Vancouver, B.C.

Barry Howson, #6, Toronto Dow Kings, London, Ont.

Fred Ingaldson, #12, Winnipeg Institute Prosvita Athletic Club Buffaloes, Winnipeg, Man.

James Maguire, #7, Toronto Dow Kings, Weston, Ont.

John McKibbon, #13, Montreal Yvon Coutu Huskie, Sudbury, Ont.

Warren Reynolds, #9, Toronto Dow Kings, Toronto, Ont.

Reugen Richman, #5, Toronto Dow Kings, Willowdale, Ont., player/coach

George Stulac, #15, Toronto Dow Kings, Toronto, Ont.

Joseph Stulac, #4, Toronto Dow Kings, Toronto, Ont.

Before making the trip, Team Canada scrounged up a scrimmage against the only two teams they could find, the Cincy Sachs Detroit All-Stars and a Latvian-Lithuanian league in Toronto who offered up an all-star team. That was only six weeks before the Olympics.

Howson admits he never felt the pressure of the moment.

“I had been tested by my coaches from the start,” he said. “My high school coach would have us run up and down the court, frontwards and backwards, as he stood at the centre of the court. I ran by once and he stuck his foot out to trip me. I fell – boom – and he laughed as I am laying there. He wanted to know how I would react. I smiled, got up, and kept running. That taught me this is what’s going to happen.

“At Western, or even the Dow Kings, they knew who the good players were, and they were going to try and upset me, break my focus. Against Toronto once, I scored and went running back down the court and the guy guarding me just punched me in the stomach; the referee didn’t even see it. Did I stop and argue? No. I kept going. A few plays later, he’s running down on a fast break, and I come up behind him and hook him. He goes sprawling. I stood over him and said, ‘Don’t you ever try that again.’

“They try to break you, break your thought. I never let them in.”

* * *

STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN, 1912

You don’t know his name. You should, but you don’t.

In 1912, John ‘Army’ Howard became Canada’s first Black Olympian when he competed at the Stockholm Games. Though his selection to the Canadian Olympic Team was historic, it was also controversial, resulting in racist coverage in newspapers of the day. He was forbidden from staying in the same hotel as his white teammates when they gathered in Montreal prior to boarding the boat that would take them across the Atlantic Ocean.

During training for the Olympics, he clashed with coach Walter Knox, who accused Howard of insubordination and threatened to expel him from the team. Thanks to an intervention by the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada, Howard stayed on the squad and made history.

Although a top-ranked sprinter in the 100m and 200m events, Howard was unfortunately felled by a stomach ailment at the Games in Stockholm. He was eliminated in the semi-finals of both events. Also a member of the Canadian 4x100m and 4x400m relay teams, he was eliminated in the semi-final and first round, respectively.

Howard served with the Canadian Expeditionary Force in the First World War and won 100m bronze at the 1919 Inter-Allied Games. His grandchildren, Harry Jerome and Valerie Jerome, were Olympians at Rome 1960 and Tokyo 1964, where Harry won bronze in the 100m.

Even drawn from sport, these are important stories about the Canadian experience, says Dr. Ornella Nzindukiyimana, a Western alumna and St. Francis Xavier University professor of sport history.

“Sport history is social history. It is about people understanding their place in the culture, in the society. If they are not told, it’s one more way to say, ‘This is only a white country, and nothing else exists.’ We lose something in not telling these stories,” said Nzindukiyimana.

“By telling these stories, we remove any notion that Black Canadians have not been around, or did not contribute, or did not make a life, did not do anything beyond struggling. It is important to highlight stories of accomplishment. It was not always about being an activist. Sometimes it was just about having a social life, about being involved in their communities, in sport.”

Howson’s inclusion on the 1964 Canadian Olympic basketball team was equally historic – a first across the previous four Games the country’s basketball team had participated in. Strangely, it is not an accomplishment that was acknowledged at the time – or even since.

“They didn’t make a big fuss despite the fact he was breaking this major barrier. How do you gloss over this major development? How do you treat it like nothing and just move on?” Nzindukiyimana said.

* * *

TOKYO, JAPAN, 1964

Although his career had taken him across the country, Howson had never traveled outside Canada until he boarded the plane for Japan in September 1964.

The Pre-Olympic Basketball Tournament determined what national teams would join the Olympic field later that month. Twelve teams. Two spots. There was plenty to play for, but Howson remembers a little extra, as well.

“As we were getting ready to board the flight to Japan, the Canadian Amateur Basketball Association (CABA) official said, ‘By the way, if you qualify for the Olympics, we’ll reimburse you your $500. He was grinning when he said that – I don’t think he had any faith in us and thought he wouldn’t be paying out.”

After stumbling out of the gate with a 20-point loss to Australia (73-53), Canada performed well enough for the remainder of the tourney, winning six of its next seven games against the likes of Thailand (70-52), Indonesia (70-60), Korea (73-65), Malaysia (88-45), Taiwan (86-79), Philippines (68-64), and Cuba (72-63), falling only to Mexico (64-61). Howson averaged 9.0 points per game in the tourney, with a single-game high of 15 in a win over Malaysia.

At tourney’s end, Australia and Mexico topped the 12-team field with 8-1 records. Normally, they would have been the only two teams to qualify for the Olympics. But thanks to the withdrawal of United Arab Republic (who qualified as 1964 FIBA Africa Championship winners) and Czechoslovakia (who qualified as fifth-place finishers in the 1960 Rome Olympics), Canada (7-2) and South Korea (5-4) squeaked into the 1964 Games.

Arriving in Tokyo, the basketball squad’s inclusion at the Olympics was so unexpected, in fact, that when the players arrived at the Team Canada athlete village, an old U.S. Army base, there was no room for them. They ended up settling into a nearby home.

* * *

Since basketball entered the Olympics in 1936, the Americans had dominated the sport. Going into the 1964 Games, the Yanks had won five straight gold medals. It didn’t look likely to change that year, as the American roster featured future NBA players Jim ‘Bad News’ Barnes, Bill Bradley, Larry Brown, Joe Caldwell, Mel Counts, Walt Hazzard, Luscious Jackson, Jeff Mullins, and George Wilson. In fact, the U.S. golden streak reached seven, before the Soviets finally beat the Americans in 1972.

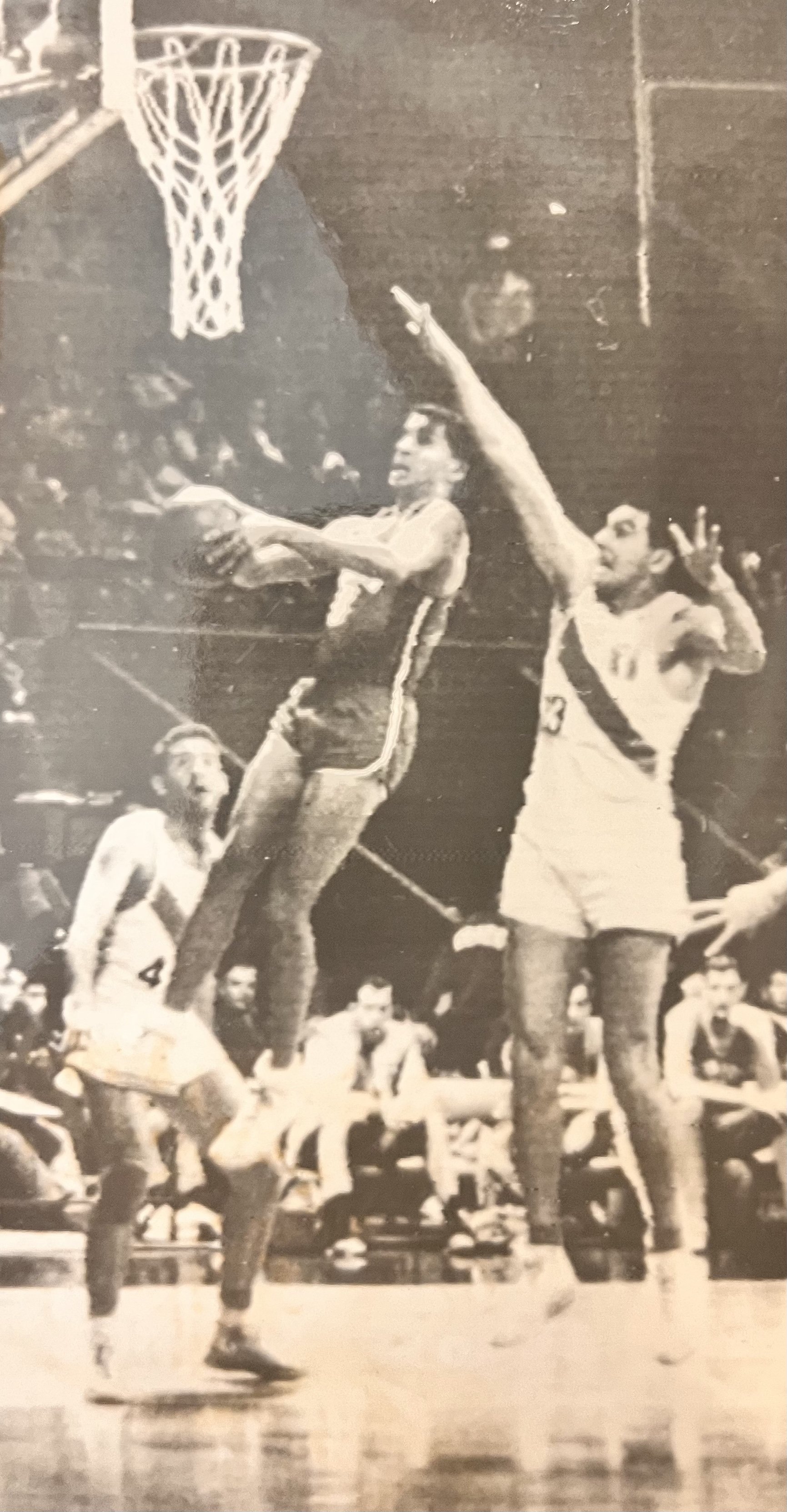

In 1964, the basketball event took place at the Yoyogi National Gymnasium in Tokyo, from Oct. 11-23.

For the Canadians, The Games proved to be a tall order immediately – with a first game Group A draw against the Soviet Union and its 7-foot-3 centre Jānis Krūmiņš. Known as the Russian woodchopper, Krūmiņš was among the first dominant big men in Europe. He had won silver with the Soviet National team in the 1956 and 1960 Games.

“You get used to the spotlight. It’s a mental thing,” Howson said. “You focus no matter where or who you were playing. Yes, the Olympics was tops. I played in a lot of championships over the years and the Olympics was big. But I didn’t approach it any differently than any other game because I believe in my mental preparedness.”

The game was never a game, as more than 3,000 fans saw the Soviets beat the Canadians 87-52 on Oct. 11, 1964. After that, the Canadians dropped six straight games in Group A to Hungary (70-59), Japan (58-37), Italy (66-54), Mexico (78-68), Puerto Rico (88-69), and Poland (74-69). It wasn’t until the Classification round that Canada nabbed its first and only win, a narrow 82-81 OT victory over Peru. They then ended the Games with a 68-64 loss to Hungary.

“We were only six weeks into practicing as a team with only two exhibition games. That’s it,” Howson said. “It’s kinda incredible we won one.”

In the Final, the United States defeated the Soviet Union to win their sixth consecutive Olympic basketball gold medal, while Brazil earned the bronze against Puerto Rico. Canada (1-8) finished 14th out of 16 teams, ahead of only Peru and South Korea.

Individually, Howson started slowly, with single-digit efforts in the first three games. After sitting out against Italy, he closed with five straight double-digit performances, against Mexico (13 points), Puerto Rico (12 points), Poland (12 points), Peru (15 points), and Hungary (12 points). Howson (10.0 PPG) finished among the team’s leading scorers during The Games, along with McKibbon (16.9 PPG) and Reynolds (11.4 PPG).

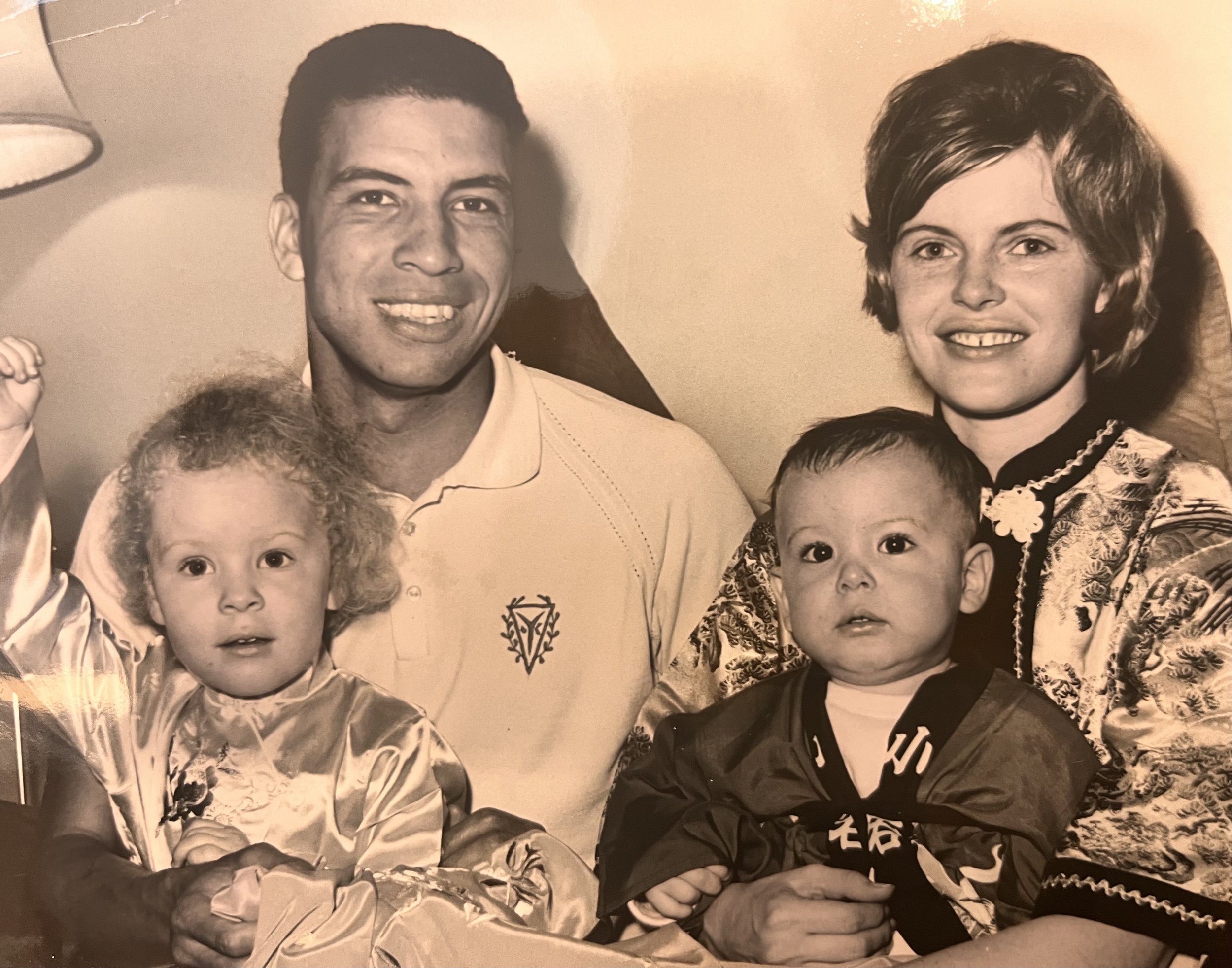

In 1964, Howson was one of three Forest City Olympians – along with swimmer Louise Kennedy and fencer Bob Foxcroft – to return home to a hero’s welcome. Howson, in fact, was featured on the sports pages of the London Free Press smiling alongside his family adorned in kimonos he brought home from The Games.

* * *

LONDON, ONTARIO, 1967

Howson never really left the court.

Even after he returned to the classroom and coaching, he continued to represent Canada at the Canada Winter Games in 1966, the Pan American Games (Winnipeg) in 1967, the World Championships (Yugoslavia) in 1971, and, more than two decades later, the World Masters Championship in Sydney in 1994.

Perhaps no post-Olympic title matched his time with the Drawbridge Inn Knights of Sarnia in 1967.

As player-coach, Howson created the Knights when his attempts to find sponsors for a Senior 'A' basketball team in London failed. So, he turned to Sarnia – and brought his talented team a little further southwest. Even half a century later, fellow Knights still credit Howson’s play and coaching as a reason they eventually won the gold, as they explained to the Sarnia Observer in 2017:

“Barry Howson was the best basketball player I ever played with,” Tom Henderson said. “I remember one game we were playing against Quebec and every time we touched the ball the hometown fans would go nuts, they would start booing us. But Barry just sort of picked the team up and carried it on his back – talk about a single-handed win. He was just amazing that game, it was one of the most amazing performances I have ever seen on the court.”

“Barry was our leader and organizer and coach. He was a great coach, and he was our best player, too,” Doug Shaver explained. “I think one of our biggest assets was our conditioning – Barry was tremendous in getting us all into shape and ready for the tournament.”

“He was actually pretty strict as a coach, as I remember,” Jerry Schen said. “He had his rules, and you didn’t cheat for fear of never seeing the floor again. But he was a good guy to play for. He knew his stuff, he treated everybody well and ran things very effectively. It was a hugely positive experience.”

Life continued for Howson off the court, as well.

Christine Jenkins Howson died May 8, 1967. She lived long enough to see Howson accomplish his Olympics feats, and much more.

The Jenkins kids proved to be an incredible bunch: Fred, David, and Christine continued their parents’ work running the newspaper. Fred was the first Black trustee elected to the London Board of Education (later merged into the Thames Valley District School Board), serving two terms in the 1980s.

Kay Livingstone was a social activist, actor, and broadcaster who helped create the National Congress of Black Women of Canada in 1973. Credited as first using the term ‘visible minority,’ her commitment to equality and social justice was honoured by Canada Post with a postage stamp in 2018.

Howson spent more than three decades as head coach of the St. Patrick’s Fighting Irish senior boys’ basketball team in Sarnia. He coached at Lambton College for five years (1972-1976) and was director and coach for the Sarnia Youth Boys Travel Basketball Program.

Despite his hoops accomplishments, he speaks at length about the joy brought to his life by his ability to influence the lives of thousands of kids – both on the court and in the classroom.

Howson has lost count of the number of Halls of Fame he has been inducted into, from the Canadian Basketball Hall of Fame and Sarnia Lambton Sports Hall of Fame. In 2013, he was inducted into the London Sports Hall of Fame, a class that included Stanley Cup champion Craig Simpson and legendary Western University coach Bob Vigars. Five years earlier, Howson had been inducted into the London Hall as a member of that historic 1957 Beck Spartans team.

With all these honours, you would think Canada would remember Barry Howson’s significance.

* * *

TORONTO, ONTARIO, 2022

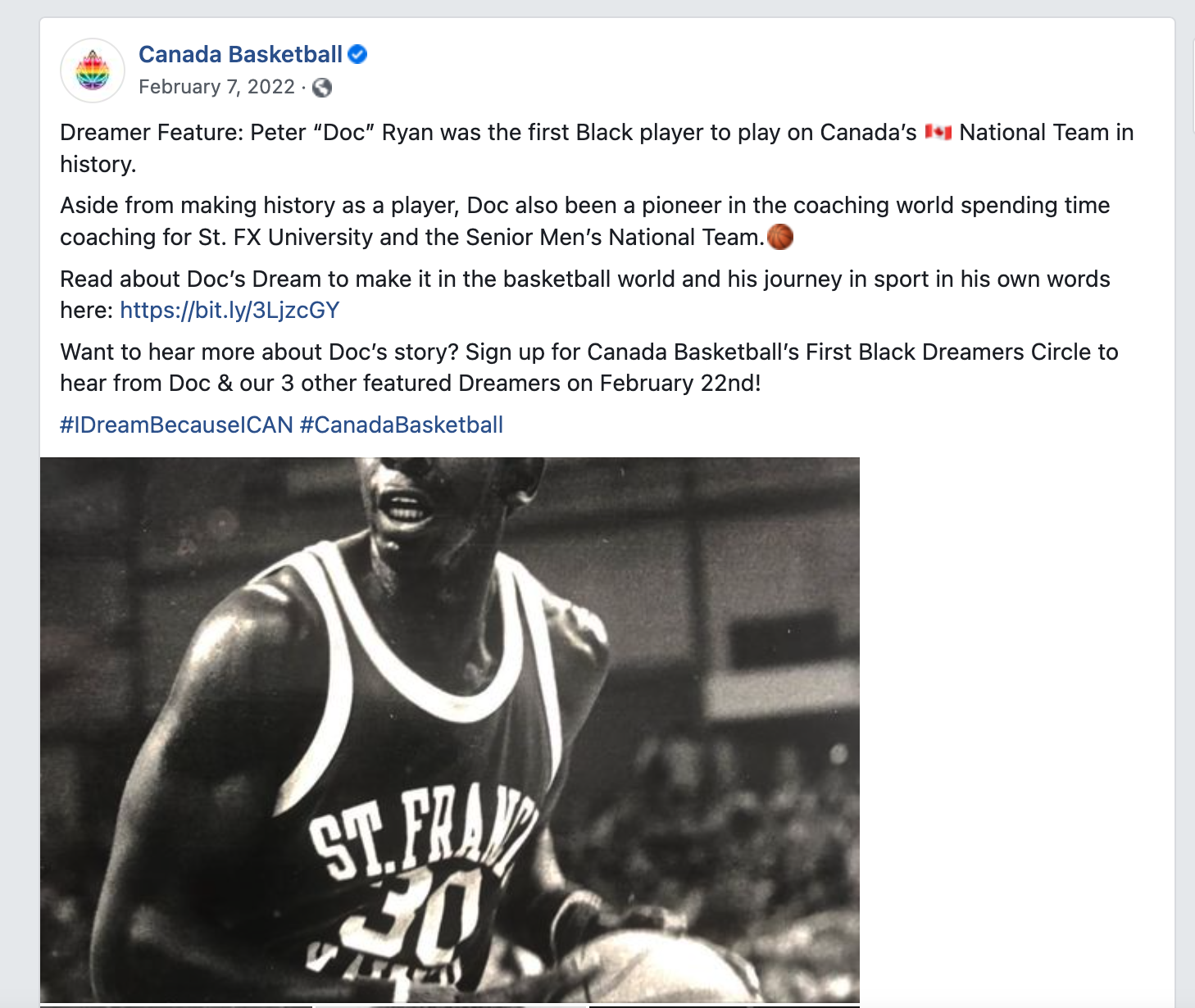

In February 2022, Basketball Canada looked to celebrate the first Canadian Black player on the national team as part of its celebration of Black History Month. Finally, the country’s governing body for the sport was drawing attention to the contributions of this often-overlooked pioneering player. A lavish story was written for the website and distributed across its social media channels.

It was an exciting day – for Doc Ryan.

Peter ‘Doc’ Ryan attended the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières (UQTR) on a partial scholarship where he led the nation with 30.6 points and 19 rebounds per game. He was named Second Team All-Canadian in 1976-77 and Atlantic University Sport (AUS) First Team All-Star in 1977-78, both with UQTR, and AUS Second Team All-Star in 1978-79 with St. Francis Xavier University.

In 1980, Ryan was named a member of the Canadian Olympic team. That team, however, never competed in the Moscow Games, as Canada joined the U.S.-led boycott.

After his playing days, Ryan spent 12 years as an assistant coach with the Canadian Men’s National Program, as well as head coaching stints with the St. FX women and Dalhousie men’s basketball teams, and as an assistant coach with the St. FX men’s basketball team. He was named AUS Coach of the Year in 1999-2000.

To be sure, Ryan has been an incredible contributor to the game of basketball in Canada. But he wasn’t the first Canadian Black player on the national team.

The oversight was even stranger given that Howson had been inducted into the Canada Basketball Hall of Fame in 2001.

“You see a lot of figures forgotten or ignored, or largely undermined, too many long dead with their families forced to fight for their loved one’s memories to be recognized,” Nzindukiyimana said. “There is almost one in every sport – one where this name has been buried or overlooked and has to be recalled later on, often much later on, as a result.”

Howson is fortunate; he is alive, well, and able to tell his story to anyone who will listen. When he noticed the Basketball Canada snub, he dropped a note to the London Sports Hall of Fame.

The Basketball Canada story has since been edited, but the error remains uncorrected. The story now reads: “What a lot of people don’t know is that Doc was also one of the first Black players on Canada’s Men’s National Basketball team. His journey to be the ‘first’ and the experiences Doc had as a player on the national team are quite a story.”

Basketball Canada has yet to officially recognize Howson as the first Black player on Canada’s Men’s National Basketball team.

* * *

SARNIA, ONTARIO, 2023

A lot of Howson’s past is still within his rather lengthy arm’s reach. The Opening Ceremonies blazer is long gone, but he still has the shoes he wore at Western, as well his Olympic jersey – which still fits nicely.

Look around his Sarnia home, and you’ll see that he is surrounded my mementoes of a successful career and a happy life. Basketballs and photographs. Binder after binder capturing so many moments. He doesn’t dwell on snubs, but then again, he doesn’t mind setting the record straight either.

“Race was never something I thought about in the moment. There were always racial things out there, but on all the teams I played on, all the way back to high school, they respected me,” Howson said.

Howson himself never really knew he’d been a pioneer until someone mentioned it decades later.

“My whole family were pioneers. My mother instilled that in us,” he continued. “I could wear any mask I want. My father’s mother was Black. My father’s father was white. I am a mix of all. I have been white, Black, even Indigenous to people. But I have never felt anything but Canadian. That’s it.”

Knight Watch: After sweeping Owen Sound, London takes on the No. 5 Erie Otters in the second round of the OHL playoffs; Columnist Jake Jeffrey previews the matchup — and predicts the rest of the OHL series …